Lydia is the Education Advisor for Bishops’ Appeal. She wrote this piece as a spark piece, effectively ignited by a reflection given by Jessica Stone from the Church’s Ministry of Healing: Ireland on tapping into God’ infinite reservoir of compassion. The result has been a joint Lenten reflection series on the theme of Compassion.

Research was carried out on a group of Divinity Students who were given the story of the Good Samaritan as the theme for a sermon and then told that they were delivering said sermon in ten minutes on another side of campus. As they rushed to make their deadline they came across a person, clearly in pain and in need of help. Every one of them stepped past the person pleading for help in order not to be late. Time and again our reasons for looking the other way, for cultivating indifference or for choosing not to see others is our busy schedules, the importance of our rushing and the things we pile into our direct vision that then excuse our ignoring of what is in our peripheral vision.

Slowing down is not lazy, it is compassionate.

Reflecting on how I structure my day, I must admit that much of my time in between the last and the next deadline is taken up with processing the previous and preparing for the next appointment, the next task, the next event. I regard this approach to my day as focused and give myself a pat on the back for my time management skills. However, if this becomes the only mode in which I engage the world, I have no doubt that I will, and have in the past, stepped over a person in need whilst on my way to advocate for the rights of the oppressed. Things or people that challenge me to divert from my carefully planned day or life can become irritants, inconveniences. Taking time to reflect, to look around, to notice others brings what is in our peripheral vision into our direct gaze and challenges us to reprioritise our time.

Often one of our reasons for not responding to others needs is because we choose not to see them. When this practise becomes habit our not noticing becomes learnt behaviour that we actively need to address in order to unlearn it. Therefore it can also be said that compassion is not so much an emotion we possess but a discipline that we craft.

With our blinkers on all we can see is a blur in our periphery, a potential inconvenience that, once we speed up, will soon be behind us and no longer pose a challenge to how we are living. I would even argue that the speed by which we live our lives is sometimes a shield that we hide behind, protecting us from the vulnerability of really engaging with others. In terms of our immediate relationships – our spouses, our siblings, our children and our friends – how easy does it become to side-line them for schedules? They are right there but we can’t really see them. We don’t take time to sit and acknowledge their presence, to insist on quality time, to schedule them into our diaries first and dig our heels in about honouring those commitments. Often we justify our actions by arguing that what we are doing is for our loved ones when actually our greatest human need is to be seen, to be valued and to belong. By that standard what our loved ones want most is our time.

Beyond the boundaries of our immediate lives, living constantly in the fast lane means that issues – global issues, human issues – become someone else’s concern. Slowing down in order to reflect means we are opened to a world that not only shapes us but that is shaped by us. And if we buy in to the rat race of work and consumerism that we are told dictates our success and our worth, we fail to join the dots and see how we are interconnected and how our not seeing means we are actively creating a disconnect. God’s call for us to love Him and love others becomes infinitely easier when we cut ourselves off from all those who do not come into our line of tunnel vision. The challenge arises when we see that tunnel vision as actively creating an injustice by removing our obligation to love others by making them invisible. A popular slogan asks the question ‘Is it Just Us? Or is it Justice?’, implying that when we keep our eyes on ourselves and do not look beyond ourselves we cannot address injustices that we cannot see. Here we are going even further by saying that we perpetrate injustices because we fail to see.

Without trying to romanticise or essentialise a continent based on one experience, my first trip to Africa as a 19 year old student was to a small town in Southern Uganda. Every morning as I walked to work strangers would stop me and engage in a ritual of asking me how I was. The questions surrounded the health of my family, how well I slept and my plans for my day. The discomfort I felt in trying to arrive to work on time whilst repeatedly being stopped meant my responses were curt and distracted. One day a minister reiterated to me a well-known modern African proverb– ‘You have the watches, but we have the Time’. The issue was not around values such as punctuality and professionalism versus tradition but around relationships and maintaining the integrity of their place in the throes of any given day.

Within the framework of this community model an individual does not exist for himself or herself; one only exists for others and as a part of a wider network. In fact, some teachings would assert that the individual does not and cannot exist without others; such is the depth of the connection. This is echoed in Ubuntu, the South African philosophy that simply states ‘I am who I am because you are who you are – I cannot live without you’. We cannot live in isolation; the blinkers must come off and we must admit to our existence only in relation to others. When we do this, we are in a place to acknowledge the areas in our fast paced lifestyles that might need adjusting in order live out the rhythm of this truth with any authenticity. We must take time to reconnect, to realign ourselves with our existence that is dependent upon those things and those people that we have relegated to our peripheral vision.

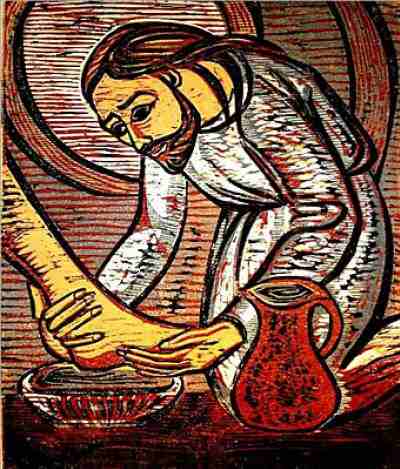

Returning to the story of the Good Samaritan, the Priest, the Levite and the Teacher of the Law were all rushing and the importance of their rush justified their skirting of the man beaten and left for dead at the side of the road. Another reading of the story sees Jesus as the suffering and bruised man on the side of the road and the person who helped him as the one who responded to the true call of God to serve, to love and live out the radical message of self-sacrifice for others in everyday life. All the Good Samaritan did was value the life in front of him, step out of his self-made rhythm and step into another more responsive mode of being. He slowed down and so deviated from his plan in order to participate in an infinitely bigger, more compassionate Plan.