Archive for year: 2013

In Grief

[new_royalslider id=”2″]

Annual Thanksgiving Service & Gift Day

Our Annual Thanksgiving Service & Gift Day with Holy Communion and Prayers for Healing will take place onWednesday, 26th June 2013, at 3.00pm in St George & St Thomas’s Church Cathal Brugha Street, Dublin 1.

The Very Revd Dermot Dunne will preach, and there will be an opportunity for prayer with the laying on of hands and anointing with oil for those who desire it.

All are welcome to join us for the service and to remain afterwards for some light refreshments.

This service is hosted with the help and contributions of the Dublin & Glendalough Diocesan Committee.

Open House & Special Service

Join us Wednesday, 29th of May, for refreshments in Egan House, where Us. (the new name for USPG) and CMHI offices are located, prior to a special celebration of the Eucharist in St Michan’s at 7.30. The Most Revd Richard Clarke, Archbishop of Armagh, will preside, and the Rt Revd Ellinah Wamukoya, Bishop of Swaziland will preach. A reception will follow, and all are very welcome to attend any and all of the above. If you plan to attend, please contact Linda Chambers (us@ireland.anglican.org), so that the appropriate numbers are catered for.

Caring for the dying: Reflecting on End of Life

We all need to love and to be loved. We all have a need for relationship and for respect. We all need to know our story has been heard. These needs come into sharp focus when we know we are dying. This wisdom was presented at the End of Life Seminar recently organised by the Revd Mark Wilson, Chaplain in Tallaght Hospital.

The first speaker of the day was the Revd Bruce Pierce who opened the seminar by leading us in a meditation that gently led us to reflect on our own inevitable death: a sombre beginning to a day of serious discussion but also interspersed with good humour and wit. Canon Neil McEndoo spoke of his work at Harold’s Cross hospice and the hope that people carry even as they face death. Dr Stephen Higgins, Consultant in Palliative Medicine, spoke of his work and the excellent care provided by palliative teams who provide medical support, spiritual support and, very importantly, treatment for pain.

Caring for the dying calls us to reflect on our own mortality as we grapple with our hope in Christ and a natural fear of the unknown, the mystery of death. Empathy is a most important quality. There is an emotional cost for those who walk with people who are dying. They too need to avail of support for their own wellbeing as they meet the challenges that arise. The Church’s Ministry of Healing is glad to offer support in whatever way it can to clergy and chaplains who are engaged in this vital work.

Signs of life: Alleluia!

We continue our thoughts on wellbeing through Easter with a new series, Signs of Life. This story is contributed by the Rev Daniel Nuzum, who serves as a chaplain at Cork University Hospital. You can find more of his writing at Soulbalm.

John (not his real name) had lived with Motor Neurone Disease for many years but over a period of months John’s illness progressed rapidly and it became obvious to John that he had little time to live. It was a huge loss when John lost the ability to use words: a vibrant man had now become silent. Now, instead of words John used his familiar ‘thumbs-up’ gesture to say that all was ok. John loved the story of the road to Emmaus and I read it with him often.

The story of the Road to Emmaus from St Luke’s Gospel is one of my favourite resurrection stories. Cleopas and his friend were walking to Emmaus in a downcast way. Jesus —unknown to them —was walking alongside them listening to them as they told his story. At the time it seemed that nothing was happening. Only when they sat down to eat and they broke bread did they suddenly recognise that Jesus was in their midst.

It is a wonderful example of how gently God can become known to us. “Were not our hearts burning within us?” they asked. In such a gentle way Jesus came alongside them and touched their hearts. This is the deep connection we experience when our inner needs are met.

I will never forget one particular evening when I came to that phrase about our “hearts burning within us” when although frail, John confidently gave his thumbs-up gesture. Here, when words would no longer flow for John somehow his gesture proclaimed louder than any speech that God was near. Our hearts burned within us.

We are not defined by illness but by the image of God that each of us radiates even when our physical bodies let us down. Alleluia!

Lent and Well-being: Enough is enough

So here we are in Holy Week, and while tomorrow, Maundy Thursday, I’ll be thinking about Jesus in the Garden, begging his friends to stay with him, to pray with him, and all the anguish that follows before we emerge blinking into the light of Easter resurrection, today my thoughts are bent in a different direction.

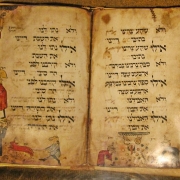

This week is not just the Christian Holy Week, but also of course the Jewish Passover. The last few years I’ve been fortunate enough to attend a friend’s Passover seder, and what’s reverberating in my head right now is one of the children’s songs traditionally sung during the meal, Dayenu. Dayenu means, roughly, ‘it would have been enough for us’ or ‘it would have been sufficient’. Some of the lyrics (in English) go like this:

Had He permitted us to cross the sea on dry land, and not sustained us for forty years in the desert, Dayenu!

Had He sustained us for forty years in the desert, and not fed us with manna, Dayenu!

Had He fed us with manna, and not ordained the Sabbath, Dayenu!

Had He ordained the Sabbath, and not brought us to Mount Sinai, Dayenu!

You get the idea. There are 15 of these stanzas, and each one concludes an affirmation: It would have been enough. Enough for what? To be satisfied? To be rescued? The Tanach Study Center explains that the answer is ‘enough to praise God’. Reason enough to celebrate. Reason enough to be grateful.

Lent gives us six weeks to eschew excess and appreciate the grace of enough before we enter a season of more-than-enough. It also gives us a chance to notice where there is most definitely not enough. Where there is not enough food, not enough love, not enough dignity. And if we find that lack in our own lives, can we find help? And if we find that lack in the lives of others, can we give out of our newly recognised abundance?

This is a reflective week. A holy one. Perhaps you’ve been contemplating the Stations of the Cross. Perhaps you’re attending Maundy Thursday and Good Friday services. I think as part of my Holy Week reflection, I’m going to try to write some of my own Dayenu stanzas, a sort of glorified gratitude list to mark the end of Lent. What would go on your list?

‘There are a thousand thousand reasons to live this life, every one of them sufficient.’

—Marilynn Robinson, Gilead

Lent and Well-being: Telling stories

I remember a much-loved literature professor impressing upon us the importance of story. ‘Why does it matter?’ he asked. ‘Because that’s what we are. You’re more than a personality; you’re more than your DNA. You’re a story, and your story is unique. Even if you and your identical twin did exactly the same things side by side for the rest of your lives, your stories would be different.’

And now we’re heading fast into Holy Week, a time in the Church year when we re-tell, and on a certain level re-live, the story most central to our identity as a faith community. And while that story is unifying, an arc big enough and transcendent enough to embrace us all, it enmeshes with our own stories to become something new and intimate. Each person’s journey towards resurrection is both like everyone else’s and very much unlike everyone else’s.

This early Easter story tells of two troubled young people and ‘the long journey we each take to go beyond what hurts toward the one who heals us’, while The Stories that Bind Us focuses on the communal story, pointing to the importance of a strong family narrative for children’s emotional health and resilience, and blogger Ellen Painter Dollar reflects on the dominant narratives surrounding disability as well as those stories it seems we’re not allowed to share.

The American radio programme, On Being, has also been talking about stories and story-telling lately. The episode entitled The Great Cauldron of Story, an interview with Harvard professor of Germanic languages and literature Maria Tatar, touches on the importance of fairy tales and legends (which she is careful to distinguish from sacred stories) in the working of our own personal narratives:

And at one point, I asked many of my students, what books from childhood they had brought with them to Harvard. And why? And what I was struck by was that often the students didn’t really remember much about the story, but there was something in the story — some little talisman. Some moment, a sentence, something a character does, a detail in a picture sometimes that they bonded with. It was almost like a little souvenir of the tale that they then carried with them into adult life. And you know, when they would think of that — everything with light.

We talked about brain sliding up that there was, and some deep connection with your childhood. And trying to figure that out was always such an interesting exercise. Because inevitably a story grew out of that souvenir. Not necessarily the story from childhood, but a new tale — their own story. And so, you know, again it became a kind of platform for figuring things out in their own lives — in their own daily lives.

Finally (I’ve saved the best for last), this interview with storyteller Kevin Kling gives me so much to think about when it comes to stories and healing that even though I’m going to put in a few excerpts here, I urge you to listen to the whole programme some time when you’re in the car, or washing the dishes, or anything that allows you to pay whole-hearted attention to the funny, gentle wisdom found in this man’s stories and reflections. If you’d rather, you can read the transcript instead.

Kling was born with a birth defect and later survived a near-fatal motorcycle accident. I love his initial exasperation with fairy tales and how he came to see them:

And the Ugly Duckling, OK, this one, this one was a particular thorn for me. Um, because, I mean, the Ugly Duckling, it’s all going great, you know, when he’s this large uber-duck. I love that, you know, this big duck. But then they find out he’s a swan. And so he, he, all of a sudden, he’s not a duck anymore. He’s a swan. Well, when you’re a kid with a disability, what does that do, hope, you know, hope a ship of aliens lands and goes, “No, you’re really one of us?” Because, you know, but you’re stuck living with ducks…And yet when I learned you could tell them the way you saw them through your own eyes, and that fairy tales were meant to be told, and told at, to get your point of view across, then I got to change them around and thicken them up.

And elsewhere:

But that’s exactly how I use stories, is that by telling a story, things don’t control me anymore. It’s in my vernacular. It’s the way I see the world. And I think that’s why our stories ask our questions, our big questions, like, “Where do we come from before life, after life?” “What’s funny in this world, or sacred?” And even more importantly, by the asking in front of people, and with people, even if we don’t find the answer, by the asking, we know we’re not alone. And I have found that often that’s even more important than the answer.

But I want to end with another resurrection story. This is Kling describing his experience after the accident when he was suffering from post-traumatic stress, and how he remembers re-awakening to life.

And I had to take an elevator down to the bottom floor every day and try to walk a half a block. That was, like, my job. And I’d walked my half a block, and my wife, Mary, met me in the lobby, and she bought an apple for me. And I hadn’t, food had no taste. So I was losing a lot of weight. And she said, “Just take a bite just for me.” So I took a bite, and flavor, that was the day it came back, and the sweetness came in, and, um, when the sweetness hit my tongue, it, I started to cry and it was flushing out all of the antibiotics and toxins that I had. I had not, again, I hadn’t cried in years. And my eyes were burning, and with my burning eyes and the sweetness in my mouth, it just felt good to be alive.